Modernist pilgrimage to Lisbon

Lisbon was not exactly brimming with modernist architecture but I did manage to seek out a church, a gallery and a public building that were of interest to me aesthetically.

Sagrado Coração Church

Fairly inconspicuous from the street, Sagrado Coração Church was tucked between residential buildings and offices with its entrance elevated above street level.

The church and its accompanying annexes were designed and built by Nuno Teotónio Pereira and Nuno Portas between 1962 and 1970 on a small plot of land in central Lisbon.

To optimise the small amount of space, the church and its annexes were distributed across a number of different levels united by a large uncovered public area connecting every entrance to the plot via different platforms.

The interior of the church was similarly multi-levelled with the different sections spread across multiple levels linked by staircases and platforms. The layout encouraged movement compared to a standard single-storey church, almost as if it was designed for people to be part of the space rather than just sitting in it.

The design was dominated by concrete and glass with striking lines running across the ceiling in a geometric pattern. The interior space was designed in such a way to allow light to filter in at the right angles to cast soft shadows and play off the textures of the concrete, which contributed to a decidedly peaceful, reflective atmosphere.

Artificial lighting by way of distinctive lantern-shaped lamps had been placed thoughtfully throughout the space to complement the natural light.

Gulbenkian Museum

The Gulbenkian Museum was part of a modernist complex in Lisbon, designed by Portuguese architects Ruy d’Athouguia, Alberto Pessoa, and Pedro Cid. Built in the late 1960s and opened in 1969, the museum was created specifically to display its collection, unlike many older museums that occupied repurposed buildings.

The design of the buildings reflected modernist principles, with low, horizontal structures made of concrete, stone and bronze-tinted glass. In 1975, the complex won the Valmor Prize for architecture, and in 2010, it was recognized as a National Monument—the first contemporary building in Portugal to receive this status.

The Main Museum Building

The main building museum was low and spread out, its concrete surfaces softened by the surrounding trees and water features.

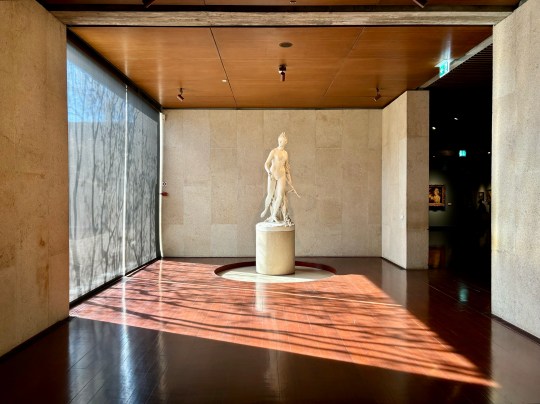

Inside, the use of wood, stone, and carpeting contrasted with the concrete exterior and large windows throughout the space framed views of the surrounding gardens and let natural light into the galleries.

The museum’s design used nature as the backdrop to both the artwork (mostly traditional in style) and architecture.

The Foundation’s Headquarters

Adjacent to the museum were the headquarters of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

This building shared the same modernist design as the main museum with a modular structure that emphasised clean lines and simple materials.

The layout consisted of large open plan areas connecting the concert halls, public spaces and administrative offices that made up the building. These vast carpeted areas were punctuated with attractive mid-century furniture, some of it built into the space.

The Gulbenkian Garden

The buildings were surrounded by the Gulbenkian Garden, a 7.5-hectare green space designed by landscape architects António Viana Barreto and Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles.

The garden was created in the late 1960s as part of the modernist movement in Portugal, using natural vegetation in a way that broke from traditional landscaping styles. It was designed to feel like a natural extension of the museum, with winding paths, open spaces, and water features that reflected the minimalist style of the buildings.

The CAM Building and Kengo Kuma’s Redesign

At the far end of the Gulbenkian garden was the CAM (Centro de Arte Moderna) building, originally designed by British architect Sir Leslie Martin and opened in 1983.

This building recently underwent an extensive redesign by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, known for his work that merges architecture with nature. His new design featured a 100-metre-long canopy made of Portuguese ceramic tiles, inspired by the Japanese Engawa—a covered walkway that creates a transition between indoor and outdoor spaces. This space housed a collection of modern and contemporary Portuguese art.

Palace of Justice in Lisbon

The Palace of Justice was a striking brutalist building, designed by architects Januário Godinho and João Henrique de Breloes Andresen.

Standing at the head of Parque Eduardo VII, a large green space in the center of Lisbon,it was built between 1962 and 1970 and serves as the city’s main court.

The building was long and rectangular, with large concrete columns supporting its cantilevered facade on all sides. This design made it look as if it was slightly lifted off the ground, giving it an unexpected sense of lightness despite its monolithic size. The materials and structure were typical of brutalism – strong, geometric, and functional – but with a unique Portuguese touch. Instead of the raw, heavy concrete often seen in brutalist buildings, the facade here was decorated with geometric patterns and rhythmic textures. This detail softened the building’s appearance, reflecting Portugal’s penchant for a patterned tile. The interplay of light and shadow on the textured concrete created a dynamic effect which must change throughout the day.

I wasn’t able to blag my way into the building, unfortunately, but was glad to visit its imposing facade in person.