Tagged: home-decor

Carl Larsson-gården (Lilla Hyttnäs), Sundborn Sweden

During a recent trip to Stockholm (which unlike neighbouring capitals Oslo, Helsinki and Copenhagen seemed to have a dearth of mid century/modernist attractions), I decided to make the long journey north to visit Lilla Hyttnäs, a late 1800s cottage and the home of Carl and Karin Larsson, in the tiny village of Sundborn outside Falun in Dalarna.

While the cottage predates the mid-century modern period that I usually focus on by over half a century, the Larssons pioneered a distinctly Scandinavian approach to domestic design (light, colour, craft and simplicity) that shaped the sensibilities later associated with Nordic modernism and the interiors (bold, bright and strikingly modern-looking for their time) became the blueprint for a whole national aesthetic. IKEA reportedly makes regular pilgrimages to the cottage: a busload of designers visits annually, mining ideas for future products and the Larssons’ influence on IKEA’s aesthetic and product line is unmistakable.

Our trip to the village and the cottage felt faintly folkloric: a three hour train journey to Falun, followed by an infrequent rural bus or a prohibitively expensive taxi to Sundborn (I chose the latter: £45 for a fifteen-minute drive) but all of this added to the sense of pilgrimage.

The village of Sundborn consisted of a scatter of deep Falu-red wooden houses along the Sundborn river with the Larssons’ home as its centrepiece. On the freezing November day that we visited, both the village and the grounds of the property were deserted and we were met by a single, very knowledgeable guide who took us on a private tour of the cottage (private because we seemed to be the only visitors to the village that day). Unfortunately, photography was not allowed inside as the cottage is still owned and very much used as a home by members of the Larsson family (small signs of life could be seen amidst the preserved, museum-like rooms) but I managed to find a lot of photos of the interiors online to accompany this entry.

Carl Larsson, born in 1853 into poverty, was lifted out of hardship by teachers who recognised his talent and helped him into the Royal Swedish Academy of Art. He worked in Stockholm, struggled, moved to Paris, struggled even more, and eventually found his footing in a rural artists’ colony outside the city. The light, the water, and the community suited him.

Meanwhile Karin Bergöö, born into a more prosperous family, trained at the Art Academy in Stockholm. She and Carl met in France, married, and eventually returned to Sweden. Karin’s father gifted them Lilla Hyttnäs in 1888: at that time a tiny cottage of four rooms and a kitchen.

What followed was a slow transformation, with extensions added between 1888 and 1912. By the time that the Larssons had settled permanently in 1900, the house had grown to about thirteen rooms, each with its own character and shaped by the interplay of Carl’s painting and Karin’s revolutionary approach to textiles, colour, and furniture design.

We began in what had effectively been the family studio-workroom. This was where Carl painted and where Karin wove textiles on her loom – the guide pointed out a folksy cushion decorated in a very contemporary looking hearts and tears motif (symbols of hope and devotion) that a designer like Donna Wilson might make nowadays.

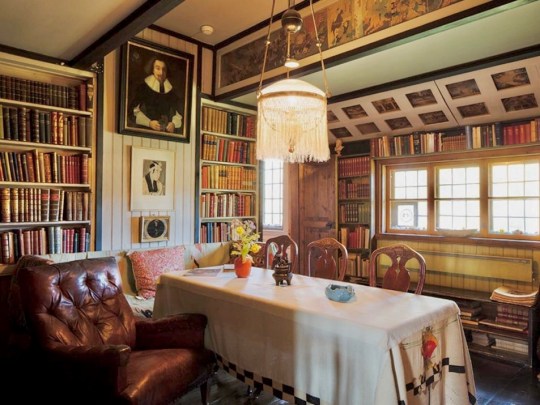

Next door was the dining room, which occupied one of the oldest parts of the house, the original cottage from the early 19th century. This space was dark and richly coloured in deep reds and greens. Meals were eaten in this room at a long table with a family-tree tablecloth designed by Karin under curling red lampshades designed by Carl. A heavily decorated cupboard known jokingly as the “cupboard of sins” (which concealed the kitchen door) stored liquid tobacco and various illicit “medicinal” alcohols.

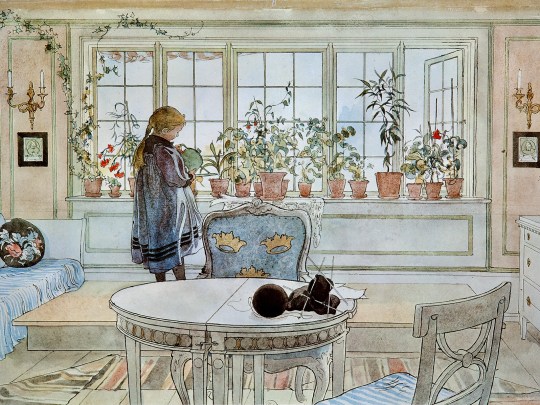

Adjoining the dining room was perhaps the most famous room in the house given that it was depicted in 24 of Carl’s paintings, including the iconic Flower Window from 1894. The living room was a warm, lived-in space with a tiled stove in the corner (above which, flowers climbing up to the ceiling had been painted) and windows overlooking the Sundborn river. The white wooden furniture and balustrades and pale blue and white textiles looked familiar, partly because IKEA’s design language is so saturated with echoes of it.

Upstairs were a number of guest rooms and bedrooms which seemed to run into and connect with one another in a warren-like manner.

A wood paneled guest room, added in 1901, was furnished with a vast floor-to-ceiling carved cupboard from a German church. A traditional Swedish box-bed sat against the wall – short, enclosed, and designed for sleeping propped upright rather than lying flat. A commode hidden under a woven cushion in the corner reminded me that this was a 19th century house though the family have reportedly added a modern bathroom to the private quarters of the building.

The family slept in two adjoining bedrooms. Karin and the younger children used a bright, white-walled nursery-like room with green painted ceilings which featured yet more familiar looking pieces (IKEA has replicated the sleigh-style bed and the iron chandelier from this room).

This room was separated by a curtain embroidered with a Rose of Love motif from Carl’s bedroom, which featured a single bed placed in the centre of the room, surrounded by textiles like a four-poster tent, with windows, cupboards, and doors lining the walls of the room. Unusually, there was a small interior window in that looked down to the studio-workshop so Carl could view his paintings from a distance.

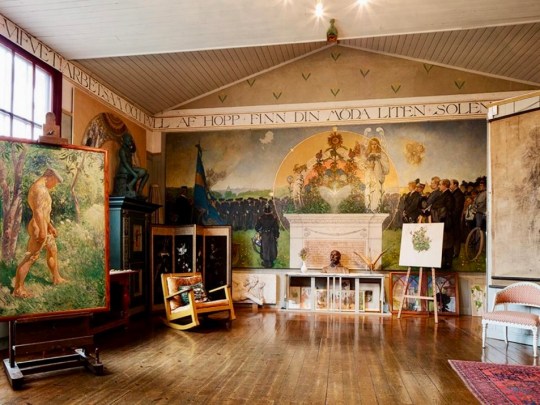

Back downstairs, a long corridor displaying works by artist friends, led to a large, dramatic studio space, built in 1889. Carl erected an internal wall to ensure the light entered only from the south, the way he preferred. A modern-looking rocking chair designed by Karin and since reproduced by IKEA (and I’m sure I’ve owned one from Habitat that looked like it) sat by the window. A tiny staircase (so narrow and steep that you’d never design one like it today) led from the studio up to additional bedrooms, another quirk that again reminded me that for all its modernity, Lilla Hyttnäs was still a 19th-century cottage at heart.

The last addition, completed in 1910, was a small cottage attached to the house used variously as a guest room and Carl’s writing room. The final sentence he ever wrote before he died of a stroke in 1919 was preserved on the desk.

Karin lived until 1928, spending summers at Sundborn until she moved to be closer to her children. In the 1930s, the Larsson children decided to preserve the house as a museum, while still using it as a holiday home. It remains hugely popular in the summer months, a living monument to the style their parents helped to create.

Stockholm round-up

As well as visiting the Larsson house, I visited another few places of tangential interest to this blog (as I mentioned above, Stockholm is not really a mid century/modernist city).

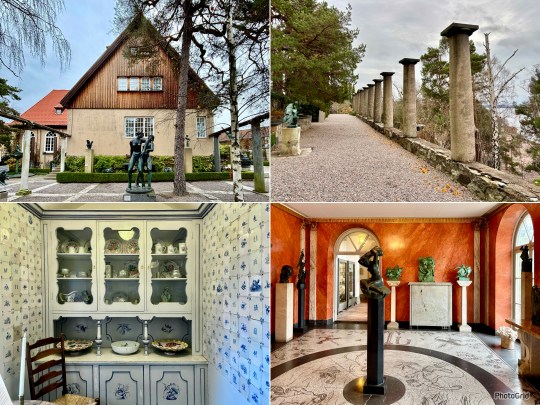

Millesgården, on the island of Lidingö, turned out to be far more expansive and stranger than I expected. The site was really three places in one: the modernist museum building, which during my visit hosted a beautifully curated Alvar and Aino Aalto exhibition; the original artist’s house, gingerbread-trimmed and storybook-like on the outside but surprisingly grand and palazzo-esque inside; and, tucked a little to the side, the 1950s cottage built for the artist’s secretary, perfectly preserved and quietly tasteful in that now-familiar Scandinavian style.

All of this was layered across terraced sculpture gardens overlooking the water, with Carl Milles’ dramatic bronzes scattered across the hillside, giving the whole place a slightly otherworldly but alluring atmosphere – somewhere between a Mediterranean villa, an artist’s fantasy garden, and a piece of mid-century time travel.

Even stranger, in a compelling, slightly uncanny way, was Sven-Harry’s Konstmuseum, a golden metal-clad building in Vasaparken that hid a full-scale replica of a floor of Sven-Harry’s own 1920s house on the roof. Walking through this simulated house complete with what looked like a working kitchen and a fake crackling fireplace, suspended above the city, felt more like stepping onto a film set or a dream reconstruction than visiting a museum. Everything was immaculate (and the domestic setting provided an unusual and unique way to display Sven-Harry’s impressive art collection) but off-kilter.

And finally, for shopping, I went across town to Ryttargatan Vintage, a sort of indoor flea market open only on weekends from 11 to 3. Compared to almost everything else in Stockholm, the prices felt improbably low. The place sold a large range of Swedish glassware, pottery, textiles, paintings, homewares and clothing.

Photo sources for images of interior of Carl Larsson house:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/20/t-magazine/carl-karin-larsson-sweden-home.html