Tagged: modernist

Modernist Pilgrimage returns

After not having posted anything in over a year (and not having been anywhere in over 18 months), the end of lockdown has meant that I’ve been able to get out and about to actually generate content for Modernist Pilgrimage.

In addition, the shabby bathrooms that we left out of our house renovation project for budgetary reasons have packed up after three years (the ensuite is currently being held together by tape) so I’ll be documenting the renovation of these as well over the coming months.

Thank you to anyone still reading Modernist Pilgrimage!

Modernist pilgrimage to Stuttgart

Although the end of our trip to Stuttgart was somewhat tainted by Storm Ciara/Sabine (we ended up holed up in a dodgy hotel next to Stuttgart airport for 48 hours waiting for a flight home), we did manage to see some excellent modernism-related sights during our time there.

Weissenhof

In 1927, an impressive line-up of 17 architects synonymous with the Modernist Movement including the likes of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Walter Gropius built an experimental residential settlement called Weissenhof, which translates as “the Dwelling”, on a hill on the outskirts of Stuttgart.

Weissenhof – two-family house designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret

The settlement, consisting of 63 apartments and 21 houses, was designed as a socialist alternative to slum housing usually endured by the poor and was intended by the architects to house modern city dwellers ranging from blue-collar workers who would presumably live in the studios and smaller apartments to members of the upper middle class who would live in the larger houses.

Weissenhof – main thoroughfare

Weissenhof – building designed by Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe

Weissenhof – Hans Scharaun, Breslau

The homes were designed to be bright spaces surrounded by verdant landscaping to promote healthy living. A key example of one of these homes was the two-family house designed by Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret on the edge of the complex, which was recently added to the UNESCO’s World Heritage List and opened to the public as a museum.

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, front elevation

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, roof terrace

The house, essentially a fancy semi, had many features closely associated with Le Corbusier including a horizontal strip window that ran across the length of the front facade, painted steel columns on the ground level which held up first and second floors, a terrace on the flat roof partially sheltered by a concrete canopy and a monochromatic colour scheme with splashes of bold colour.

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, museum space on left side of building

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, roof terrace

Visitors entered the building via the house on the left hand side of the semi. This house had been converted into a whitewashed museum with a modified floorplan to accommodate an exhibition setting out the genesis and history of the Weissenhof. Having climbed the modernist staircase through three floors of this rather bland museum space, you were directed down into the second, more interesting house by way of the roof terrace that connected the two houses.

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, living space on right side of building

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, bathroom on right side of building

The second house was laid out, furnished and decorated as it would have been in 1927. The not very substantial living area was located on the middle floor and consisted of a kitchen, bathroom and living/sleeping area with staff quarters occupying the whole of the ground floor. Apparently designed with women in mind, the spaces were narrow and simply furnished.

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, sleeping area on right side of building

Weissenhof – Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret house, living area on right side of building

Neue Staatsgalerie

The Neue Staatsgalerie was designed by the British firm James Stirling and was constructed between 1979 and 1984. The controversial building, consisting of a series of connected galleries around three sides of a central rotunda, has been described as the epitome of Post-modernism.

Neue Staatsgalerie, exterior at night

The building was a slightly disorienting and trippy mixture of classicism (travertine and sandstone in classical forms) with modernist elements (industrial pieces of slime green steel and bright pink and blue steel handrails) and housed a collection of 20th century modern art including Picassos, Modiglianis and Schlemmers.

Neue Staatsgalerie, interior lobby

Neue Staatsgalerie, dancers of Oskar Schlemmer

Vitra by StoreS

I know it’s hugely overpriced and everything that they sell is a well-worn design cliche but I can’t help but love Vitra.

Vitra by StoreS, inside

At 570sq metres and spread over two levels, the colourfully fronted Vitra store that we visited on Charlottenplatz was the world’s largest retail space dedicated to Vitra. As well as stocking all of Vitra’s design cliche products (displayed as attractively as ever), the store also looked at the company’s history in the form of a small museum of sorts.

Vitra by StoreS, inside

Vitra by StoreS, Vitra map

Wurttembergische Landesbibliothek

The State Library of Württemberg was designed by Horst Linde and opened in 1970. An academic library, it contained the humanities sections of the University of Stuttgart.

State Library of Württemberg, interior from first floor

I couldn’t find any information online about the building which suggests that it isn’t held in particularly high regard but I thought the exterior and interior spaces were visually quite striking in terms of design and scale. It also looked like it hadn’t been renovated since 1970, which greatly appealed to me.

State Library of Württemberg, interior from main entrance

Flea market Karlsplatz

As far as European fleamarkets go, this was a good one. Open every Saturday since 1983, Flohmarkt Karlsplatz filled the whole of a large square, consisting of well over 100 stalls selling everything you might expect from a typical flea market including mid-century furniture, antique frames, crystalware ornaments, silverware, crockery, antique kitchen appliances, antique cameras, WW2 militaria, coins and toys.

Flea market Karlsplatz – mid century ceramics stall

My favourite kind of stall has always been the type that looks like the vendor has cleared out their own home and dumped it on a table (and there were plenty of stalls like this here) but there were also some slightly more professional dealer-types with higher quality tat mixed in which gave the flea market a slightly higher end feel.

Flea market Karlsplatz

Flea market Karlsplatz – Eames chairs

Modernist Pilgrimage to Phoenix

Phoenix, Arizona was a bit of a step down in the glamour stakes after Palm Springs (it only factored into our plans because it was en route back to London) and we’d made the foolish mistake of coinciding our visit with Thanksgiving Day in the US (which explains why most of the photos in this blog entry look like something out a post-apocalyptic film) but it turned out that there was a lot to like about the place from a mid century/modernist perspective.

Fifth Avenue Medical Building, 1967

Dental Arts building, 1969

Phoenix Financial Centre, 1964-72

Armed with our map from modernphoenix.net (a spectacular, if slightly overwhelming resource setting out every modernist building of interest in the city), we wandered around taking in various commercial buildings.

Pyramid, 1979

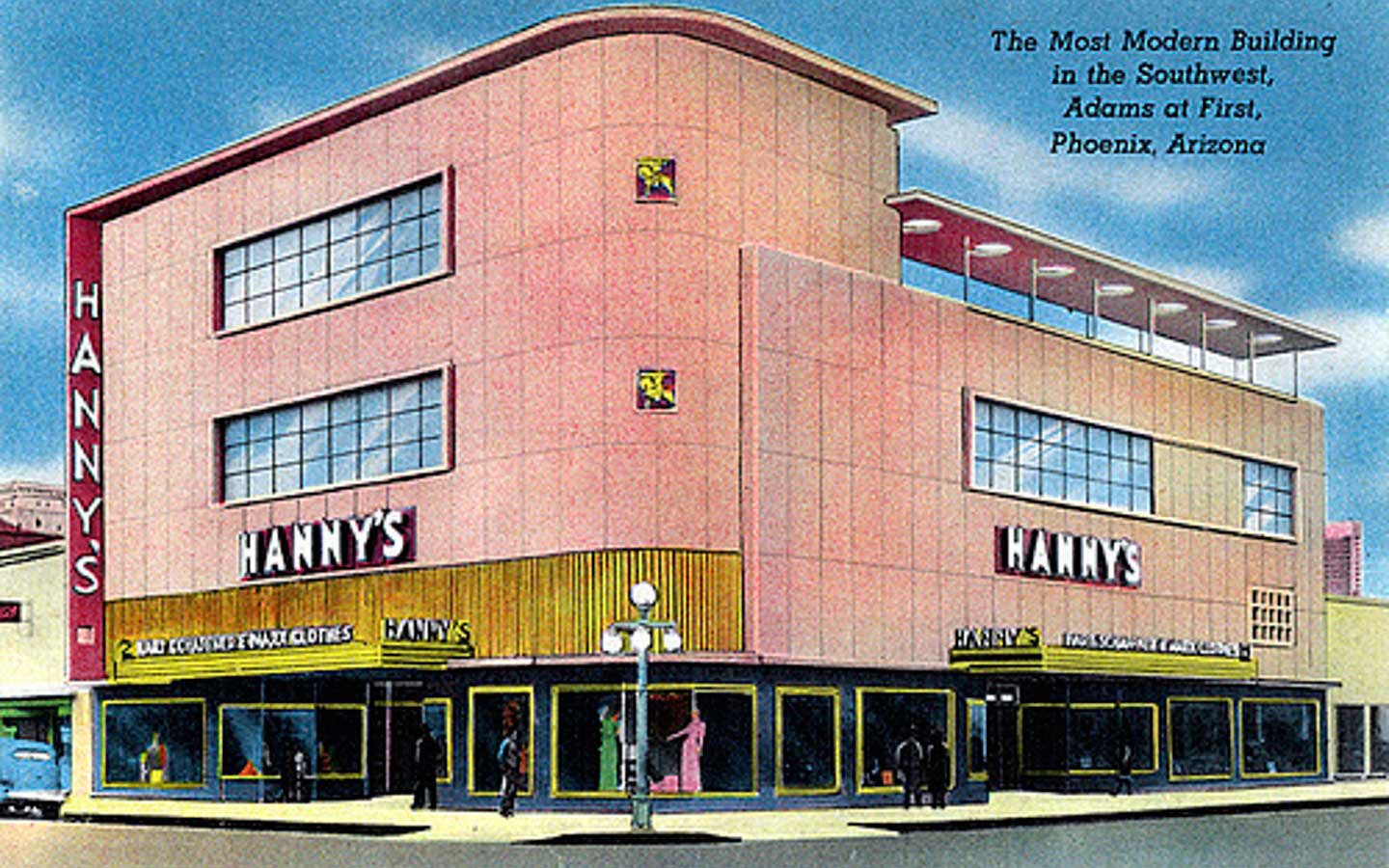

Hanny’s, 1947

US Federal Building and Courthouse, 1961

This included Hanny’s (formerly a department store, now a restaurant) from 1947 with its international-style facade, the US Federal Building and Courthouse from 1961, Central Towers (often referred to as the “U-Haul Towers” since U-Haul’s headquarters are located there) from 1959-62, Pyramid on Central (basically a concrete inverted pyramid) from 1979, the Lescher & Mahoney office (a two-storey courtyard office building occupied by an architectural firm) from 1963, the Phoenix Financial Centre together with the “North Rotunda” and the “South Rotunda” (today used as government offices) from 1964-72, Durant’s (a longstanding steak restaurant) from 1950, the Fifth Avenue Medical Building from 1967 and the Dental Arts building (essentially a box on silts, a popular design solution in Phoenix for providing shaded parking while maximising the leasable area of an office building) from 1969.

Durant’s, 1950

Lescher & Mahoney office, 1963

Unidentified building, 1950-60s

Central Towers, 1959-62

We came across some futuristic-looking mid-century motels featuring dramatic angles, bold colours and oversized neon signs, the best example of this being the City Centre Motel (now a Travelodge) from 1959. Most of these had been left to ruin and had a distinctly seedy feel upon closer inspection.

City Centre Motel, 1959

In contrast, we also came across a concentration of nice garden apartment buildings from the late 1950s/1960s on Fifth and Sixth Avenues. These garden apartment buildings were characterised by a low-rise profile, the incorporation of a central open space, generous patios and balconies (designed to provide shade for the unit below) and a general blurring of the line between indoor and outdoor spaces. These garden apartment buildings mostly had glamorous park-like names such as Park North, Royal Riviera, Park Fifth Avenue and The Shorewood.

The Pierre Apartments, 1961

In terms of shopping, we discovered a cluster of around ten decent but not especially bargain-filled mid century/vintage stores along N Seventh Avenue.

Modern on Melrose, 700 W Campbell Avenue

Modern Manor, N 7th Avenue

Mod Curated Modern Design, N 7th Avenue

Perhaps most significantly of all, Phoenix was home to several Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, two of which we visited – First Christian Church and Taliesin West.

First Christian Church, 1973-78

First Christian Church, 1973-78

First Christian Church was first designed around 1950 for a local client which went bankrupt. The design was revived by First Christian in 1970, long after Frank Lloyd Wright’s death and was completed in 1973. Meant to “evoke the Holy Trinity and reflect an attitude of prayer”, the chapel’s roof and triangular spire were 77 ft high, supported by 23 slender triangular pillars. The church was accompanied by a separate and free-standing 120 ft bell tower built in 1978 and topped with a 22 ft cross.

Taliesin West, 1937

Taliesin West, 1937

Slightly further afield was Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s winter home and architectural school. This bizarre building warrants its own dedicated blog entry, which will follow.

Vintage photo of US Federal Building and Courthouse, 1961

Vintage photo of City Centre Motel, 1959

Vintage drawing of Hanny’s, 1947