Tagged: modernist

Sybold van Ravesteyn House, Utrecht

Tucked into a small triangular plot a few minutes down the down from the Rietveld Schröder House was the intriguing Sybold van Ravesteyn house. Built out of sand-coloured railway bricks between 1932 and 1934 by Sybold van Ravestyn (an eccentric architect best known for designing train stations for the Dutch Railways), the house challenged architectural conventions of the time.

The plot – little more than a wedge-shaped leftover at the bend of a street – was just about big enough to fit the house, which consisted of a rectangular two-storey building with a semicircular volume and roof terrace on the first floor. A narrow garage – almost comically tight – was appended to the left side of the property, designed to form part of the overall silhouette of the house.

Inside, Van Ravesteyn maximised use of the small footprint by using narrow, steep stairs and installing curved walls to soften corners and guide movement around the house.

The central part of the house was a large open plan living space with no dividing walls between the study, sitting room and dining room – an unusual concept at the time and one of the first examples of modern open plan living in the Netherlands.

This large open-plan space featured curved lines in the floor, a suspended ceiling of frosted glass in a steel frame and built-in furniture, which served to subtly zone the space into sitting, dining and working areas.

Though the house was practical in many ways (unusually for domestic buildings at the time, it had both central heating and plumbing throughout the house and a kitchen equipped with modern domestic appliances), Van Ravestyn resisted the cold minimalism often associated with early modernism, filling it with porcelain figurines, neo-Baroque decorative lines carved into the ceilings and built-in shelves that drew the eye across the room, their lines continuing into baseboards and shutter grooves.

Upstairs were three bedrooms and a bathroom. Van Ravestyn decided against installing traditional box beds in the bedrooms (still common in Dutch homes of the era) in favour of more modern free-standing beds flanked by built-in closets. The master bedroom featured a circular window with a bespoke shutter and an enormous terrace – larger than the bedroom itself.

Each of the son’s bedroom and the guest room (where the family’s nanny stayed during her pregnancy, having been impregnated by Van Ravestyn himself – though this could have been a mistranslation!) each had their own basins and nightlights.

Van Ravesteyn lived in the house until his nineties after which it was acquired and renovated by the Hendrick de Keyser Association. It has since served as a house museum and can be booked for overnight stays – something which gave the house a distinctly “lived in” feel.

Rietveld Schröder House, Utrecht

Visiting the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht was like stepping into a physical representation of a Mondrian painting.

Built in 1924 by the innovative architect Gerrit Rietveld (also famous for his Mondrian coded Red and Blue chair), the house was designed to be as much an artistic statement as a house in response to a brief from Truus Schröder-Schräder, a wealthy widowed mother of three with a penchant for avantgarde design.

Rietveld, influenced by the De Stijl movement, aimed to create a space defined by flexibility, openness, and clarity. Though it was constructed during the same period as the traditional brick townhouses that surrounded it, it broke entirely from convention and is perhaps best known for its distinctive layout consisting of an adjustable open plan space that could be divided into separate rooms via a system of sliding panels.

Exterior

Despite being brick-built, the house looked as if it was made from concrete with its clean, white plaster surfaces and intersecting planes giving it a strikingly modern appearance even today. The building stood in sharp contrast to the neighbouring houses (and the terrace that it bookended) due to its abstract, cubic form and bold accents in red, black, and yellow.

A thin red line across the façade of the house highlighted where to deliver parcels, blending functional design with visual clarity, a typical Rietveld detail. Also noticeable were structural beams and posts that ran from outside the house to inside, seamlessly connecting the interior to the exterior and a speaking tube that allowed Truus Schröder-Schräder to communicate with visitors at the front door from the first floor without having to go downstairs.

Ground Floor

The ground floor followed a traditional layout, divided into rooms for practical functions like cooking, working, and storage. The hallway was compact with a short flight of white steps leading upward beside a built-in bench. A wall unit accommodated storage for four occupants, and the coat rack was designed with both high and low sections, catering to both adults and children.

The kitchen was equipped with features far ahead of its time: one of the first dishwashers, wall cabinets with sliding glass doors, a drop-down shelf by the window for deliveries and detachable shutters on the windows. The thick exposed pipes on the wall gave the room a modern, slightly industrial feel.

The kitchen flowed through into the maid’s room, painted a cheerful sunny yellow to counteract the distinct lack of light. Unusually for the time, this room was wired for electricity and had its own sink and direct access to the garden, reflecting the importance placed by Rietveld and Truus Schröder-Schräder on maintaining independence and dignity for domestic workers. Later, this small space was rented to students.

Also on the ground floor was a workspace and a front room featuring a distinctive ceiling lamp, the design of which drew the eye upward, helping visitors perceive the three-dimensional volume of the room.

First Floor

The first floor contained the most distinctive features of the house. Designed as a space for living during the day and sleeping at night, it was officially listed as an attic to sidestep local building regulations.

This was necessary because the whole of the upper floor was an open plan space with no fixed walls that could be divided into separate rooms using sliding and revolving panels, or left open as a single large area. A central living room, originally boasting panoramic views (now somewhat obscured), featured built-in storage (including a striking yellow cupboard in the corner resembling a modernist sculpture), a skylight and the same three dimensional ceiling lamp as the one on the ground floor.

The daughter’s bedroom was designed to be multi-functional: a sitting room by day, and a bedroom for two by night. The son’s room was more experimental with a floor made from a patchwork of different colours and materials and detachable wall panels in lieu of curtains for privacy. An early version of a spotlight illuminated the room, showing Rietveld’s interest in modern lighting techniques.

The main bedroom, used by Schröder herself, was surprisingly the smallest in the house. Rietveld, however, used the space very efficiently, incorporating a built-in washbasin, a fold-out cupboard and a narrow red shelf just wide enough to hold a watch or small personal items.

The bathroom was tucked between the mother’s and daughters’ rooms and featured a granite hip bath and a sliding vent hatch for fresh air—compact, yet luxurious for the time. The separate toilet was tucked away behind a black painted door.

Though the family was wealthy, the house was decidedly modest in size, built on a tight urban plot. The constraints caused by the small plot were part of the creative challenge for Rietveld, who embraced the opportunity to build something innovative without the luxury of unlimited space and scale.

Truus Schröder-Schräder lived in the house until her death in 1985. The house was then restored by Bertus Mulder and now is a museum open for visits, run by the Centraal Museum. It has been a listed monument since 1976 and UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000. An exhibition on the house and Rietveld’s other designs form part of the permanent collection at the Centraal Musuem in central Utrecht.

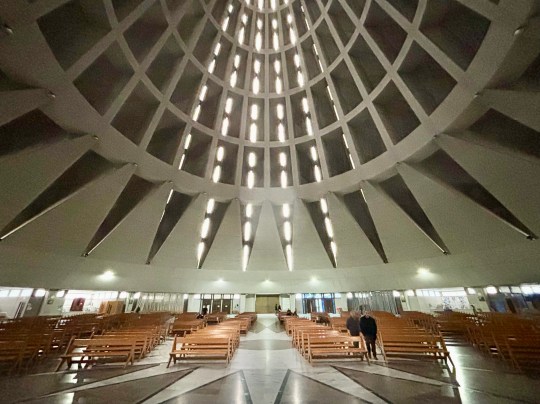

Basilica of the Madonna delle Lacrime, Syracuse

Although no one associates Sicily with modernist architecture, I visited the striking concrete Basilica of the Madonna delle Lacrime (Sanctuary of the Virgin of Tears) during a recent trip to Syracuse.

Designed by French architects Michel Andrault and Pierre Parat, the basilica was the winning entry in an international competition involving architects from 17 different countries. Construction began in 1966 but wasn’t completed until 1994 due to the building’s complex engineering, archaeological discoveries, funding issues, and controversy surrounding its bold modernist design.

Though originally intended to be even taller, the structure still reached 103 metres, its reinforced concrete cone tapering sharply upward and crowned with a bronze statue of the Virgin by Francesco Caldarella. The result is compared to a teardrop falling from heaven or, less flatteringly, to an upside-down ice cream cone. Approaching the basilica, the first impression was one of scale. The exterior was monumental and unmistakably modern, its geometric form visible from almost anywhere in the city.

Inside, the space was vast yet calm. The interior was circular in plan, 71 metres in diameter and designed to hold up to 11,000 standing or 6,000 seated visitors. Sixteen chapels were positioned around the perimeter, while the central altar – crafted from white marble and local Modica stone by Giancarlo Marchese – held the image of the Madonna delle Lacrime alongside an 18th-century cross. The interior’s height and symmetry were softened by diffused natural light entering from above.

The basilica’s striking ceiling featured a dramatic radial pattern of concrete ribs that rose and tapered toward the centre, drawing the eye upwards.

The design of the basilica was, and remains, controversial. Some see it as an eyesore, others as a daring and spiritually resonant work of modern architecture.

Winscombe Street terrace, N19

The next property I visited as part of Open House 2024 was Winscombe Street, a small terrace of houses that was the first of three housing projects that Neave Brown built in the UK.

Built on a site in 1965 over a former sewer, Winscombe Street terrace consisted of 5 three-storey identical houses and a studio. It struck me as a private and quite exclusive place to live – photography was not permitted on the Open House Tour (except for at the front of the houses) so I have used sales listings and architectural journals to illustrate what I saw inside and around the back.

The tour started on the ground floor, which contained the kitchen/dining area and a bathroom, all in original condition.

In the hallway was a very distinctive wooden staircase consisting of steps cantlivered from a central pole which anchored down into the concrete on the lower ground floor. The staircase led upstairs to the top floor and downstairs to a lower ground floor.

The upstairs floor, which consisted of two large rooms divided by a sliding partition door, was used by the owner as a living room and the master bedroom. This floor was very bright owing to the domed skylight above the staircase. We were told that this floor gets a bit too warm in summer.

The lower ground floor consisted of a half bathroom (containing a Japanese sized bath), a bedroom, a utility room and a large flexible room containing sliding doors affixed on a system of rails and tracks. This could be arranged as two narrow bedrooms or one larger space. We were told that this downstairs space was often used by residents for children’s bedrooms or a granny annex as it was self contained (with its own entrance into the back garden) and separate from the rest of the house.

Outside was the communal garden, which was well maintained by the residents via a system of clearing days during the year. We were told that the residents abide by self-imposed rules not to play any music, hang washing or erect fences in the garden.

We were told that the residents of Winscombe Terrace are leaseholders but shareholders of a freehold company responsible for the overall maintenance of the terrace. The residents struck me as a close, quite exclusive community- we were told that prospective buyers need to submit an application to the existing residents and undergo an interview process with each existing resident granted the power of veto, which is reportedly exercised every so often if the prospective buyer is not deemed the right fit.

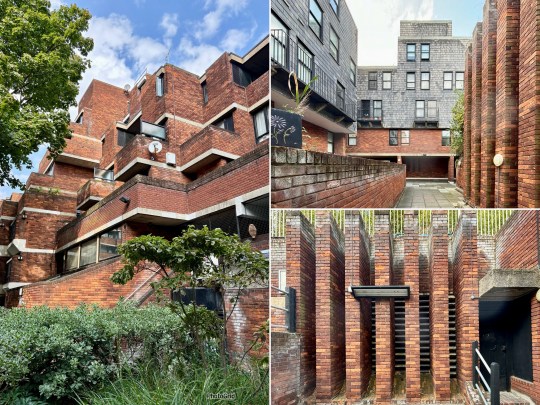

Lillington Gardens, London SW1V

I visited Lillington Gardens, the Grade II listed modernist estate in Pimlico, for the first time as a part of Open House London in September 2024.

The estate was constructed in three phases between 1961 and 1971 and was designed by Darbourne (aged only 21 at the time) and Darke.

The design was inspired by the Victorian red brick of the arts and crafts-style Grade I-listed Church of St James the Less, which is situated on the site. This was an unusual design choice in the 1960s – I don’t think I’ve ever seen another completely red brick modernist estate before.

Consisting of 1,000 homes, the intention behind the design of the estate was to provide high density housing without any high rise blocks. The plan of the estate consisted of clusters of blocks no taller than 8 storeys connected by internal courtyards and cross-wings threaded through with paths and ramps with the higher levels accessible by brick-paved internal streets.

We were led around the estate as part of the Open House tour, starting from the community centre in the middle of the estate and around the extensive communal grounds, which included a basketball court, on multiple levels.

We were not shown inside any of the apartments but were told that they ranged from studios to much larger four bedroom homes clustered in groups of three with interlocking “scissor” floor plans. I found some interior shots via old estate agent listings for a studio and a three-bedroom split level apartment, which give an idea of the size and shape of the homes.

The apartments were designed to have aesthetically pleasing views – Darbourne and Darke wanted residents to have views over the communal gardens wherever they were in the estate and installed large plate glass windows in the apartments to give them panoramic views.

Unfortunately, the apartments built in the third phase later on in the project (grey slate cladding) had much smaller windows, potentially a cost saving measure.

Residents reported that the estate was a well designed, pleasant, quiet place to live in a fantastic location. However, residents also mentioned the various issues that have plagued the estate (and have been reported on extensively) in recent times.

Faro 20th Century Society Tour

I attended an excellent C20 Society tour of Faro earlier this year, which provided me with some much needed material for this neglected blog.

The tour, led by Richard Walker (whose similarly excellent tour of the less sunny Elephant and Castle I attended in 2018), focused on the often overlooked modernist architecture that characterises the capital of Portugal’s Algarve region.

During the mid-20th century, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, many European countries experienced a wave of modernisation and urban development. Portugal was no exception and Modernist architecture, characterised by its functional design, use of new materials and minimalist aesthetic, became popular in Faro during this time.

Largely shaped by the prolific architect Manuel Gomes da Costa, Faro’s architectural landscape came to consist of a blend of European Le Corbusier-inspired design, Brazilian tropical modernism and a bit of Palm Springs glamour, adapted for the Algarve’s sunny, coastal climate.

Although a little careworn in places, it made for a very photogenic and interesting city.

Hotel Aeromar

The tour began at the Hotel Aeromar, built by Da Costa in the 1970s. While Da Costa primarily focused on private residences, he took on this hotel project only to disown the design when it was deemed necessary to replace his intended flat roof with a pitched roof due to the coastal location (the wind and water would not have been kind to the original design).

The hotel bore signs of a number of his design trademarks, especially the brise soleil-style windows which cut out sunlight but allowed it to filter through.

The facilities were basic and the decor on the dated side but it still managed to be quite charming. Apparently it once provided the backdrop for a Hermes fashion shoot – I can only imagine they were going for a kitschy vibe – but I haven’t been able to track down the photos.

Beginning the Tour

The first leg of the tour involved walking around the art deco district (consisting of 1930s low rise, box shaped buildings with a nod to classicism), and modernist districts (dominated by buildings designed by Da Costa and architects that he influenced) of Faro.

Despite Faro’s rather erratic listing system, most of the modernist buildings built in the city between the 1930s-1970s were still standing. Faro, we were told, is not a city obsessed with redevelopment and is slowly waking up to its modernist past and the potential to use it for tourism.

Faro’s buildings featured a lot of pattern and texture with an emphasis on graphic statement tiles and paving. The closely packed buildings, squeezed onto small plots, each had visual interest of some kind.

We were told that Portuguese architects like to build statement architecture but with a degree of restraint, pulling back from overt showiness. A few eye catching exceptions aside (including a rather gaudy pop art inspired yellow house), I found this to be true – this was modernism through a Portuguese lens.

The Modernist Aparthotel

The first of the interior stops on the tour was The Modernist, a once rundown brutalist building turned aparthotel following renovation works by the Portuguese architecture studio PAr.

The building was originally built in 1977 by a family who lived on the top floors and rented the rest to commercial tenants until 1986. The building, which was for a long time regarded as the ugliest in Faro, then lay abandoned until 2016.

We were told that PAr adopted a very purist approach to the three year renovation project, breathing new life into the building whilst respecting its DNA. The most significant structural change involved adding a flat rooftop (previously a traditional pitched roof), which served as a terrace offering 360-degree views of the city, including multiple Da Costa designs and Faro’s oldest department store. The original plan was to install a pool on the newly flattened roof but this was scuppered by a construction issue.

Inside, the hotel apartments were of varying size but were all largely identical – open plan studio spaces incorporating a living area (overlooking the street), kitchen island, sleeping area (overlooking the internal courtyard), small bathroom and balcony. The style was very much minimalist with simple, functional furniture built into the walls (including an Alvar Aalto-inspired curved window ledge) and a largely monochromatic colour scheme consisting of green, red and gold.

The materials used throughout (mostly locally sourced wood and stone) were natural and tactile. It was all very pleasant and tranquil but the lack of various modcons (including a tv – a conscious decision by the owners) meant that I’d probably struggle staying there…!

Casa Gago

The next building that we saw the inside of was the rather spectacular Casa Gogo.

Casa Gago was commissioned by Alfredo Gago Rosa, a wealthy emigrant from Venezuela, who wanted a special house in the heart of Faro for his family. Despite being relatively inexperienced, a 34 year old Da Costa was chosen to lead this rather ambitious project, which resulted in one of the most iconic modernist buildings in Faro.

Da Costa’s goal was to create something new with the house, akin to something seen more commonly in the US. Using Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies Van der Rohe as inspiration, the resulting building was a mix of American and tropical featuring pop art tiles, organic shapes and Aztec and Mayan motifs.

At some stage, the house was split into three levels and sold off. The second floor was used for many years as a hairdressers (there was still evidence of some of the fittings that had been left behind) before it was bought as a residential apartment by the current owner.

Thankfully, this appeared to be someone who wants to undertake a full scale renovation project to restore the apartment to its former glory – there would be nothing stopping someone from ripping out the entirety of the interior as only the exterior of Casa Gago is listed.

The owner certainly has a lot to work with, given that the apartment had pretty much all of its original 1950s features intact even if some of these features were in need of repair.

The apartment featured a number of Da Costa hallmarks – full-height doors, Z-shaped stairs a large porch, room dividing built-in furniture, glass walls and enormous interior pivot doors.

The layout was split into public (living, dining and reception rooms) and private (four bedrooms) sections with sunbreaking breeze block cobogó all down the west side.

Other buildings in Faro

The tour moved on to other buildings in the city including:

⁃ A 1966 design on a triangular plot built for a South American bank – this was considered to be a radical design at the time.

⁃ Da Costa’s own house from the mid 1960s – this was not what I expected. Inspired by Mies Van Der Rohe and a Japanese garden, it was low level and quite modest in comparison to the rest of his designs that dominated the city. The house was connected to a studio space in which Da Costa worked largely alone.

⁃ A lovely row of Da Costa villas, one of which was owned by the new owner of Casa Gago.

Another, currently used as a hotel, had been significantly remodelled to slightly underwhelming effect – the house had lost its carefully calibrated proportions and looked a bit “heavy” as a result.

⁃ Various social housing schemes, which looked well designed and quite attractive.

⁃ An intersection of buildings from the late 1970s, including one of Da Costa’s last works from the late 1980s (he stopped working shortly after but lived until 2016).

As Da Costa was never one to follow trends, this building didn’t look very 1980s at all apart from some slightly fussy looking classical columns.

Olhão

The second day of the tour took us to nearby Olhão, a cubist-looking town a short train ride away from Faro.

The courthouse and cubist buildings in Olhão reflected a different architectural language to Faro with flat roofs and grid-patterned streets influenced by Moorish design.

The old part of town contained buildings from the 1920s to 1930s covered in now-familiar patterned tiles across six streets.

The modernist part of town looked a lot like Faro except without an abundance of Da Costa designs – there was only one Da Costa house in the whole of the town.

Praia de Faro

The tour concluded with a walk along the Faro’s coastal line to take in the seafront architecture, mostly post-1959 as this was when the bridge providing vehicular access to this stretch of land was built.

The buildings ranged from basic beach huts to a sophisticated Da Costa design, heavily influenced by Le Corbusier (note the hole in the roof to accommodate the tree).

Other notable designs included:

⁃ A very charming single storey orange coloured house (architect unknown).

⁃ A heavily cantilevered blue beach house from the late 1970s built by a partner of Da Costa.

⁃ A very photogenic Air Bnb house which has featured in every news story about modernist architecture in Faro.

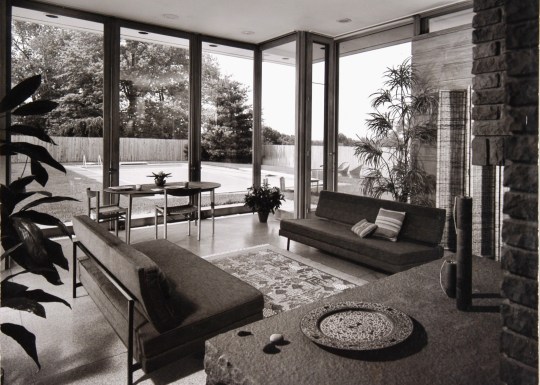

Gropius House, Lincoln MA

One of the last stops on our 2022 trip to Boston was the Gropius House in the town of Lincoln, Massachusetts, named after the celebrated architect and the founder of the Bauhaus school of design in Germany.

The Gropius House was built as a family home in 1938 and was a collaborative effort between Walter Gropius, his wife Ise and their friends who contributed Bauhaus art to the house. Having faced the closure of the Bauhaus school by the Nazis, Walter Gropius sought refuge in London before eventually settling in the US. Although he was unable to bring his monetary assets with him, he managed to secure permission to transport his furniture collection which means that the house now contains the largest Bauhaus furniture collection outside of Germany.

Originally advised to reside in Boston’s Beacon Hill, the Gropius family desired a more open and spacious environment which led to them choosing the leafy town of Lincoln. With a vision to create a Bauhaus-inspired home, the family received $20,000 from Helen Storrow, the prominent American philanthropist, which allowed them to transform a hilly apple orchard into what is now considered an architectural marvel.

Inspired by the New England landscape, Walter Gropius envisioned a house that blended the principles of the Bauhaus movement with the local materials and construction methods of the region. The wooden frame construction typical of the area was enhanced with shiplap, a colonial-style cladding and field stones at the bottom. The compact 2,300-square-foot Gropius House represented a New England interpretation of the Bauhaus aesthetic, defying convention with its shoebox-like design without a pitched roof—a radical departure from the norm at the time and which wasn’t always up to dealing with the challenges posed by the New England climate. The floorplan was carefully designed without corridors and modern materials (such as glass bricks, cork floors and porous plaster materials to enhance acoustics) were used throughout to maximise functionality.

We entered the house on the ground floor into an entrance hall containing an open coat rack, (displaying clothing that enhanced the room’s aesthetic), wide balustrades, a powder room, a door leading to the basement and a winding staircase with a bent steel balustrade leading up to the first floor.

To the right of the entrance hall was the study space, which was intentionally positioned on the northern side to avoid excessive sunlight and contained a double desk imported from Germany. This room also included a separate entrance door for clients, reflecting Gropius’ intention to use the house as a teaching tool to showcase his approach to design and construction.

The study space flowed into the living room, which looked out onto the surrounding environment through two large plate glass windows – an unusual feature for a house in New England. Most of the furniture in this room including the iconic Butterfly stools, daybed, standing lamps and the Womb chair, were designed by Marcel Breuer, a protege of Gropius at the Bauhaus.

Around the corner in the L-shaped living room was the dining area, zoned by a curtain, which allowed for dinner to be dramatically unveiled (I really think this should be brought back as a trend). The dining chairs were Marcel Breuer prototypes – the Gropius family often tried out out new furniture prototypes while living in the house, providing a unique opportunity to witness the evolution of design firsthand.

Dinner would have been prepared in the narrow but carefully designed galley kitchen, which was laid out to ensure everything as within easy reach and contained appliances (garbage disposal, dishwasher, cooker, and refrigerator) that would have been modern for the time. The kitchen had a “cold” section (the section nearest the door) and “warm” section (at the rear of the room towards the window) with the cold section acting as a buffer to keep kitchen smells contained (again – a great idea that is due a comeback). The metal cabinets were reportedly sourced from a medical catalog.

Upstairs, were three bedrooms and two bathrooms accessed via an expansive upstairs landing.

The master bedroom contained a heated dressing area with built-in table and an ensuite bathroom featuring his and hers sinks. The Gropius family believed that sleeping in natural air was optimal and so left the windows in the sleeping area open to allow fresh circulation throughout the night, which meant that it would get quite cold during winter months. I wasn’t sure about the grey, black and red colour scheme in this room – there was something of the 1980s about it.

The guest bedroom was next door with two single beds lined up against one wall, for guests to sleep toe-to-toe or head-to-head.

Gropius went above and beyond for his daughter’s bedroom, giving her a glass roof, separate entrance to the house and a personal roof deck.

The architectural overhang and sunshade allowed for cross ventilation, while the arts and crafts desk provides a nod to traditional craftsmanship. The room could also be divided into different spaces with curtains.

Outside the house was a small covered terrace where the Gropius family had meals and played table tennis. The surrounding perennial garden, inspired by both New England and Japanese aesthetics, reflected Walter Gropius’s love for blending cultures and nature.

The Gropius family lived in the house until 1969 and after Walter Gropius’s death, his wife Ise continued to live there until she died in 1983. Today, the Gropius House is managed by Historic New England and is open to the public for tours.

Gores Pavilion, New Canaan CT

Our trip to Boston last year also included a stop at New Canaan CT, home to the Glass House that I visited in 2016 and the recently restored Gores Pavilion, which I discovered is open to the public for tours courtesy of the The New Canaan Historical Society.

The building was designed as a pool house in 1959 by Landis Gores, one of the Harvard Five, a group of architects (John M. Johansen, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, Philip Johnson and Eliot Noyes) that settled in New Canaan, Connecticut in the 1940s.

Gores was commissioned to design and build the pool house by a wealthy couple on the grounds of their lavish estate which was later sold to the town of New Canaan to become Irwin Park.

The structure consisted of a central high-ceilinged reception room flanked by two wings containing bathrooms, changing rooms and storage.

Gores installed transom windows around the sides of the reception room, which made the roof look as if it was floating, and floor-to-ceiling glass sliding doors, which were designed to slide into wall pockets and run in front of the transom windows.

The sliding doors opened onto what was originally a pool area and the reception room contained a kitchen area at the back.

When the town purchased the estate it had planned to demolish the building. At this stage, the pool house had not been used in many years and had fallen into major disrepair: vines had grown over the walls and a tree was poking out of the chimney, bursting the brick apart.

While the original pool was filled in, the New Canaan Historical Society rescued the building through private donations and a grant from the state of Connecticut Department of Culture and Tourism. The two side wings were repurposed into gallery spaces and the main reception room was restored back to its original condition in order to be a living museum for modern architecture.

Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Cambridge MA

During a recent trip to Boston, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to visit the only building that Le Corbusier designed in the US.

Never mind that the building in question was the decidedly ugly Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Forming part of Harvard University’s campus, the reinforced concrete building was completed in 1962 and was designed to inspire art and creativity at Harvard.

Sandwiched between more traditional red brick Harvard campus buildings, the site that Le Corbusier had to build on was relatively small resulting in a compact, roughly cylindrical structure bisected by an S-shaped concrete ramp going up to the core of the building on the third floor containing various glass-walled studios and exhibition spaces. The ramp was supported by a few pilotis and cantilevered from a central spine containing a lift.

I generally love and celebrate all concrete buildings but the prominent ramp and rainwater stained concrete facade gave the Carpenter Center more than just a slight resemblance to a multi-storey carpark.

Unfortunately, Le Corbusier never actually saw the completed building and declined his invitation to the opening ceremony due to his ill health.

Halsbury Close, Stanmore HA7

Another new entry on the Open House programme for 2022 was this beautiful Grade II Modernist House in Stanmore designed by architect Rudolf Frankel for his sister in 1938.

The two storey family home was built from brick rather than reinforced concrete like most Modernist houses of the time, perhaps attributable to the slow acceptance of Modernist architecture in Britain with brick being seen as a more traditional choice.

The ground floor was mainly taken up by the living and dining areas which opened out onto the garden via a cutaway veranda with a single column at the corner to support the upper floor. The kitchen, which contained the original cabinetry and maid bell system, was positioned next to the tradesman’s entrance and still-intact service wing.

Upstairs were the bedrooms and two bathrooms, one of which was largely original.

The internal layout was arranged to allow the living and dining rooms to face out onto the garden to take advantage of the southerly orientation whereas the kitchen and bathrooms were located on the northeast and northwest sides of the house to enable all drainage to be kept out of sight and the front elevation to be clutter-free.

Extremely well preserved, the house was owned by two generations of the family who acquired the house from Frankel’s sister until 2019 when it was bought by the current owners, who seemed equally committed to preserving the house’s original features. Not that they have much choice in the matter: the Grade II listing (which describes the house as one of the most elegant and least altered private houses erected before the War) means that all alterations need to be approved before they are made, including relatively small details such as the choice of tile in the bathrooms and kitchen.

The lack of ornamentation in the design and the abundance of original features from the original build (flooring, light fittings, light switches, radiators, floor finishes, ironmongery and joinery) gave the house a timeless, contemporary quality.