Category: Open House

Winscombe Street terrace, N19

The next property I visited as part of Open House 2024 was Winscombe Street, a small terrace of houses that was the first of three housing projects that Neave Brown built in the UK.

Built on a site in 1965 over a former sewer, Winscombe Street terrace consisted of 5 three-storey identical houses and a studio. It struck me as a private and quite exclusive place to live – photography was not permitted on the Open House Tour (except for at the front of the houses) so I have used sales listings and architectural journals to illustrate what I saw inside and around the back.

The tour started on the ground floor, which contained the kitchen/dining area and a bathroom, all in original condition.

In the hallway was a very distinctive wooden staircase consisting of steps cantlivered from a central pole which anchored down into the concrete on the lower ground floor. The staircase led upstairs to the top floor and downstairs to a lower ground floor.

The upstairs floor, which consisted of two large rooms divided by a sliding partition door, was used by the owner as a living room and the master bedroom. This floor was very bright owing to the domed skylight above the staircase. We were told that this floor gets a bit too warm in summer.

The lower ground floor consisted of a half bathroom (containing a Japanese sized bath), a bedroom, a utility room and a large flexible room containing sliding doors affixed on a system of rails and tracks. This could be arranged as two narrow bedrooms or one larger space. We were told that this downstairs space was often used by residents for children’s bedrooms or a granny annex as it was self contained (with its own entrance into the back garden) and separate from the rest of the house.

Outside was the communal garden, which was well maintained by the residents via a system of clearing days during the year. We were told that the residents abide by self-imposed rules not to play any music, hang washing or erect fences in the garden.

We were told that the residents of Winscombe Terrace are leaseholders but shareholders of a freehold company responsible for the overall maintenance of the terrace. The residents struck me as a close, quite exclusive community- we were told that prospective buyers need to submit an application to the existing residents and undergo an interview process with each existing resident granted the power of veto, which is reportedly exercised every so often if the prospective buyer is not deemed the right fit.

Lillington Gardens, London SW1V

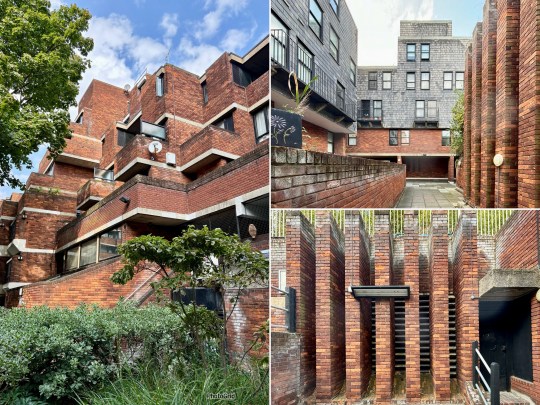

I visited Lillington Gardens, the Grade II listed modernist estate in Pimlico, for the first time as a part of Open House London in September 2024.

The estate was constructed in three phases between 1961 and 1971 and was designed by Darbourne (aged only 21 at the time) and Darke.

The design was inspired by the Victorian red brick of the arts and crafts-style Grade I-listed Church of St James the Less, which is situated on the site. This was an unusual design choice in the 1960s – I don’t think I’ve ever seen another completely red brick modernist estate before.

Consisting of 1,000 homes, the intention behind the design of the estate was to provide high density housing without any high rise blocks. The plan of the estate consisted of clusters of blocks no taller than 8 storeys connected by internal courtyards and cross-wings threaded through with paths and ramps with the higher levels accessible by brick-paved internal streets.

We were led around the estate as part of the Open House tour, starting from the community centre in the middle of the estate and around the extensive communal grounds, which included a basketball court, on multiple levels.

We were not shown inside any of the apartments but were told that they ranged from studios to much larger four bedroom homes clustered in groups of three with interlocking “scissor” floor plans. I found some interior shots via old estate agent listings for a studio and a three-bedroom split level apartment, which give an idea of the size and shape of the homes.

The apartments were designed to have aesthetically pleasing views – Darbourne and Darke wanted residents to have views over the communal gardens wherever they were in the estate and installed large plate glass windows in the apartments to give them panoramic views.

Unfortunately, the apartments built in the third phase later on in the project (grey slate cladding) had much smaller windows, potentially a cost saving measure.

Residents reported that the estate was a well designed, pleasant, quiet place to live in a fantastic location. However, residents also mentioned the various issues that have plagued the estate (and have been reported on extensively) in recent times.

Memphis double bill

Memphis: Plastic Field at MK Gallery

The Memphis design collective and its output between 1980 and 1987 (a series of often colourful postmodern furniture and design) is pretty far removed from modernism (some considered it to be a reaction to the by then stale modern movement) but I’ve always been intrigued and seduced by its bizarre aesthetic that I’ve long associated with 1980s music videos and the homes of evil rich people in Hollywood films.

Drawing from influences as diverse as India, Africa, California, gas stations, movies, music and art, Memphis design and architecture was intended to look artificial, playful and a bit uncanny.

I attended a very comprehensive Memphis exhibition at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes all the way back in 2021 (when some of the Covid restrictions had been lifted), which showcased the best of the movement’s pieces including Masanori Umeda’s Tawaraya (a boxing-ring-shaped bed), Michael Graves’ Plaza dressing table and stool (resembling a space ship made out of children’s wooden building blocks) and Ettore Sottsass’ Carlton room divider/extremely non-functional bookcase.

One room was dedicated to a screening of the scene set in Danny DeVito and Bette Midler’s Memphis-adorned house in the 1986 film Ruthless People.

Despite the fact that everything looked like it was mass produced out of colourful MDF, all Memphis pieces were individually crafted by Italian workshops and were very much intended to be sold as luxury items (both David Bowie and Karl Lagerfeld were fans). They are now hugely collectible fetching huge sums (ranging from around £5,000 – 40,000 per piece) when they go up for auction.

Brockley House

I more recently visited Brockley House as part of Open House 2024 in London.

Brockley House was a colourful (and Memphis-inspired) renovation of an end-of-terrace 1930s house in Lewisham. The design, conceptualised by architects Office S&M drew inspiration from cakes, American diners, digital art and of course, Memphis.

Over the course of an 8 month renovation project, Office S&M reconfigured the original 1930s layout into an open plan living space incorporating a candy hued cartoon-like kitchen and striking curved wall in keeping with the original 1930s architecture.

The exterior of the house was painted various shades of lilac offset by brightly colored drainage pipes, chequerboard-patterned tiles and a sculpted porch at the front with a striking pink hood supported by yellow columns.

The owners said that while there was some scepticism from passers-by when the build started (as the house sits on a corner plot on a busy junction, it certainly stands out) but neighbours have been positive about the eye-catching design.

Open House 2023

For last September’s Open House Festival, I visited three rather lovely houses – one on a development I’ve previously visited, one on a development that I’ve passed but not taken a proper look at and one on a development that was completely new to me.

Mallard Place

Having attended a very comprehensive C20 tour of the Span estates of Blackheath in 2018, I was keen to see Mallard Place in Twickenham, Eric Lyons’ final project that was initiated in the mid-1970s and completed posthumously after his death in 1982.

Mallard Place was a very distinctive estate, comprising large split-level apartments and generously proportioned townhouses on a significant riverside plot.

The estate backed onto a communal bank with spectacular river views from the townhouses that lined the edge of the water. The estate also had a communal swimming pool.

Having dabbled with a more postmodernist style (e.g. the controversial and as yet unlisted Streetfield Mews (1984) and Birchmere (1982) in Blackheath with their odd 1980s details), Eric Lyons returned to his earlier, more modernist style with Mallard Place. With their clean lines and extensive glazing, Mallard Place’s terraced houses and apartment blocks clad in hung terracotta tiling evoked Eric Lyons’ first (and listed) estate – Parkleys in Ham, Richmond (1954). The only concessions to a more decorative 1980s style were some curved archways, brown window frames and slightly fussy balcony balustrades.

The house itself was split over three storeys (four including the basement utility room and integrated garage). The ground floor consisted of a handsome split level living area with the kitchen at the front and the living room at the back opening onto a small patio which backed onto the communal river bank. The patio looked rather alarmingly close to the water but the owner explained that effective measures had been implemented to prevent the water from reaching the house.

The first floor contained the original avocado bathroom suite and three bedrooms, the largest of which had a balcony looking out over the river.

The top floor was a large fourth bedroom with a vaulted ceiling and another terrace, also facing out over the river.

Oakfield Gardens

The exterior of Oakfield Gardens formed part of Ian McInnes’ 20th Century Society tour of the Dulwich Estate but I’d never been inside one of the houses until this year’s Open House.

Designed by Austin Vernon and Partners and built by Wates, the first of the 14 houses that make up Oakfield Gardens was completed in 1958 and marked Wates’ debut in the area.

The two storey houses were L-shaped and arranged in short terraces perpendicular to the road. The original layout of the house incorporated the kitchen and living room on the ground floor and three bedrooms upstairs.

The owner of this particular house had wanted to add a fourth bedroom to the house but wasn’t able to extend upwards due to conservation area rules imposed by the Dulwich Estate. As such, they relocated the kitchen from the front of the house to a rectangular extension connecting to the living room at the back, overlooking the garden. The old kitchen was turned into a further bedroom.

Other familiar features typical of an Austin Vernon and Partners house included the open tread staircase, large plate glass windows and woodblock parquet flooring. The owner had, however, replaced the traditional warm air heating system with something equally unobtrusive: slimline radiators built into the skirting boards – apparently, popular in hospitals but still fairly unusual for residential properties. I would definitely have done this in our house if I’d known it was an option!

Tollgate Drive

The final property was a single storey ranch bungalow on Tollgate Drive (also known as Ferrings), which I had previously visited as part of Ian McInness’ Dulwich Estate tour in 2021.

This particular example of a ranch bungalow had been extended in the 1980s to build more living space in the courtyard front garden between the house and the garage. The house was further extended in 2008 to incorporate a below ground extension with a south-facing light well at the entrance to let natural light into the lower ground floor. The basement extension housed a reception room, bathroom and a very organised storeroom.

This house had been extensively refurbished, the walnut kitchen being of particular note – it had a nifty moving shelving unit which could be used to close off the kitchen from the dining area.

Halsbury Close, Stanmore HA7

Another new entry on the Open House programme for 2022 was this beautiful Grade II Modernist House in Stanmore designed by architect Rudolf Frankel for his sister in 1938.

The two storey family home was built from brick rather than reinforced concrete like most Modernist houses of the time, perhaps attributable to the slow acceptance of Modernist architecture in Britain with brick being seen as a more traditional choice.

The ground floor was mainly taken up by the living and dining areas which opened out onto the garden via a cutaway veranda with a single column at the corner to support the upper floor. The kitchen, which contained the original cabinetry and maid bell system, was positioned next to the tradesman’s entrance and still-intact service wing.

Upstairs were the bedrooms and two bathrooms, one of which was largely original.

The internal layout was arranged to allow the living and dining rooms to face out onto the garden to take advantage of the southerly orientation whereas the kitchen and bathrooms were located on the northeast and northwest sides of the house to enable all drainage to be kept out of sight and the front elevation to be clutter-free.

Extremely well preserved, the house was owned by two generations of the family who acquired the house from Frankel’s sister until 2019 when it was bought by the current owners, who seemed equally committed to preserving the house’s original features. Not that they have much choice in the matter: the Grade II listing (which describes the house as one of the most elegant and least altered private houses erected before the War) means that all alterations need to be approved before they are made, including relatively small details such as the choice of tile in the bathrooms and kitchen.

The lack of ornamentation in the design and the abundance of original features from the original build (flooring, light fittings, light switches, radiators, floor finishes, ironmongery and joinery) gave the house a timeless, contemporary quality.

Alton Estate, Roehampton SW15

An in-depth tour of the Alton Estate, a large council estate situated in Roehampton, southwest London, was a new entry on the 2022 Open House programme. Designed by a London County Council design team led by Rosemary Stjernstedt, the estate consisted of a variety of low and high-rise apartment blocks divided into Alton East (completed in 1958) and Alton West (completed in 1959).

The Alton East Estate consisted of point blocks and low-level housing (e.g. wide townhouses) designed for the 1950s demographics of the time: a lot of single people and daughters (who had lost their partners in the war) living with their mothers with less of an emphasis on families with children.

Notable sections of the Alton East estate included Horndean Close, a cluster of staggered houses around a communal green, a fashionable idea in the 1950s designed to evoke the feeling of a village green in which the local community could gather. This layout was also cheaper to build because there was no need to factor in a roadway, which wasn’t a problem as most people didn’t own a car in the 1950s before mass car ownership caught on. The use of timber and concrete (used to material shortages in the 1950s) combined with the trees (the original Victorian trees were retained and further trees added at the time the development was built), gave the close an almost Scandinavian feel.

Other notable parts of Alton East were the Swedish-inspired ten-storey tower blocks built atop a hill on the estate, emphasising the steepness of the hill and contrasted with staggered two storey blocks in a different colour. Oliver Fox, the chief architect, based the design of these tower blocks on similar blocks built in Gothenberg and Stockholm and the Lubetkin-designed Highpoint in Highgate: four flats per floor built around a central staircase and lift with internal bathrooms (by the 1950s, electrics lighting was good enough to light internal bathrooms) and sticking out external balconies (like Highpoint but not Alton West – see below). The planting around the blocks was intended to give this part of the estate a northen European/Scandinavian flavour and the differing tile patterns at the entrance of each block was intended by Cox to give each block a distinctive identity.

Moving onto Alton West, this part of the estate was considered by many British architects to be the crowning glory of post-World War II social housing at the time of its completion in 1958, largely as a result of its response to its unique setting. Built on a large expanse of parkland on the edge of Richmond Park, Alton West contained a number of different housing configurations: twelve-storey point blocks with four flats per floor (these had internal covered balconies unlike the towers in Alton East); terraces of low-rise maisonettes and cottages (including a terrace of striking bungalows built to accommodate pensioners, a relatively new social group from the 1950s onwards – before, elderly people would either live with families or, more depressingly, in work houses) and, perhaps most recognisably, five eleven-storey slab blocks, heavily influenced by the Unité d’Habitation buildings by Le Corbusier, completed in 1952 and now Grade II-listed. I understand that Alton West (and more specifically, Minstead Gardens, one of the terraces of pensioner bungalows) was used as a filming location in the 1966 dystopian drama film Farenheit 451.

The five eleven-storey slab blocks turned sideways to Richmond Park (they were originally meant to face out onto park but it was decided that this would look like a vast wall from a distance).

Housing inside consisted of flats and maisonettes, many double height with bedrooms on the upper floor (people in the 1950s still insisted on going upstairs to bed) just like in Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation buildings. Unlike the Unite d’Habitation buildings, however, these were just residential blocks with none of the communal “streets” of shops and facilities (or a rooftop paddling pool) in Le Corbusier’s designs.

Set apart from the five slab blocks built on the park land but very similar looking was Allbrook House, the very last building built on the estate in the early 1960s when economy was at its height. Allbrook House had a library with a distinctive curved ceiling at the bottom. This building has not been protected by the Grade II-listing and is scheduled for redevelopment in the near future.

Alexandra Walk, London SE19

Open to the public as part of the 2022 Open House festival (and also currently listed for sale) was this extended single-storey bungalow in Gipsy Hill.

The original development was designed by Rosemary Stjernstedt for Lambeth Council in 1968 and consisted of a terrace of angular, pale-grey brick single storey dwellings grouped around a paved communal courtyard.

Following a bit of online sleuthing, I discovered that this bungalow originally had an L-shape configuration into which four small bedrooms and separate living and kitchen areas were squeezed. This L-shape opened onto a large rear garden.

An extension in 2022 by architect Niki Borowiecki added an extra wing to the bungalow, turning the L-shape into a U-shape by eating into the rear garden. The U-shape comprised a more open plan living area and kitchen (with a small courtyard garden at the rear), three much larger bedrooms, two bathrooms and study area, all wrapped around a central courtyard garden.

I liked the house: it was very bright (helped by the use of materials throughout), the enclosed nature of the central courtyard garden made it feel like a genuinely inside-outside space that would be very useable throughout most of the year (with the help of an outdoor heater in winter of course) and the living spaces and layout flowed well.

The house is currently on sale for £885,000 via The Modern House.

Vanbrugh Park Estate

I’ve been attending Open House weekend for a couple of years now so I’ve seen the most of the modernist estates that usually form part of the programme. I was therefore pleased to be able to visit Vanbrugh Park Estate this year, which for some reason has never come up on my itinerary.

Vanbrugh Park Estate was built in 1962 and designed by the renowned architects Chamberlin, Powell & Bon responsible for the better known and more celebrated Barbican and Golden Lane estates. Set on seven acres of land bordering Greenwich Park, Vanbrugh Park Estate comprises a mixture of dwelling types: an eight-storey tower block containing 64 flats, low-rise terraced houses, and maisonettes arranged over garages.

Like many parts of London which now contain modernist architecture built in the 1960s, the area, mostly renowned for large period villas, was bombed during the Second World War and was in need of new housing. As such, careful consideration was taken by the architects when building the new housing to respect the surrounding areas, including the blind-wall terraces that were intended to reflect Greenwich Park’s own wall using similar brickwork. In addition, simple but functional materials (such as the breeze block facades) were used to save on costs so that more could be spent on landscaping communal areas, giving the estate a more utilitarian than luxurious feel – more Golden Lane than Barbican, if you will.

Two properties were open when I visited. The first was one of the maisonettes over the garage blocks. The apartment was reached via a communal walkway and comprised a conservatory-like entrance area, kitchen, living/dining area, bathroom and two bedrooms. The owners were clearly architecture and design enthusiasts and had restored a number of original features in the apartment including the wood panelling, black vinyl floor tiles and fireplace in the centre of the living area.

The second property was one of the low-rise terraced houses. Set over three floors, the entrance of the house opened onto a semi-open plan living, dining and kitchen area with stairs down to a bedroom and the garden and stairs up to two further bedrooms and a bathroom. There wasn’t much left in the way of original features in this house (the central fireplace had been removed and that bannister is definitely not original) but it was deceptively spacious and still architecturally interesting.

Ethelburga Tower

Next on the 2021 Open House itinerary was Ethelburga Tower, a 1960s 17-storey concrete framed block of flats near Battersea Park designed by the LCC Architects Dept with Ove Arup & Partners as consulting engineers.

The block was built to accommodate 98 homes: 32 split-level maisonettes on the east and west sides of the building and 17 one bedroom single level flats and 17 two bedroom flats single level flats on the south side.

The decision to have landings on odd floors, opening onto double height access galleries (with flats on the “mezzanine” floors reached by the staircase) added a bit of interest to the architecture.

The first residents moved into the block in 1967 with council tenants buying up flats under the government’s “right to buy” legislation from the 1980s onwards.

In 2009, Mark Cowper, a photographer who was living in Ethelburga Tower at the time, staged an exhibition of photographs at the Geffrye Museum (now the Museum of the Home) of individual living rooms in Ethelburga Tower, which highlighted how differently each resident had decorated their flat.

Despite not being part of the official Open House programme (only the corridors and communal areas were open to the public), an owner of one of the split-level maisonettes kindly let me have a nose around as I was passing by.

The flat was in the same configuration as those featured in Mark Cowper’s project with an entrance hall opening onto the living room with glass-panelled door leading onto a small balcony and adjoining kitchen on the lower floor and a staircase leading up to two bedrooms and a bathroom on the upper floor. There was also a cupboard on the upstairs landing containing a fire escape staircase leading to the roof (though I may have misheard this).

Walters Way, London SE23

This year’s Open House weekend included access to Walters Way, a close of 13 self-built houses on a sloping, tree filled site (not unlike Great Brownings) in South East London.

Each house on the close was built in the 1980s using a method developed by Walter Segal, the celebrated Swiss architect. This method involved the use of a modular, timber-frame system reminiscent of 19th-century American houses or traditional Japanese architecture.

Although the houses were all built using the same method of construction, the houses were designed with flexibility and individuality in mind. Unlike Great Brownings, where homeowners are required to ensure that their house looks the same as all of the others on the estate, I was struck by the way in which all of the houses on Walter’s Way were unique in both style and configuration (most of having been adapted and extended since they were built).

We were invited to have a nose around two of the houses on the estate, which timber walls and flooring aside, were quite different owing to changes made by the owners to the layout and sun deck/garden patio areas outside.

The owners of one of the houses (self-build house 1 in the photos) had extended with lean to lobby which was self-built and a more substantial two-storey extension which wasn’t – whilst more straightforward than a regular build, self building using the Segal method is apparently not without its challenges.

One of the key considerations was the retention of supporting posts from the original build – here, they made for a design feature across the middle of the living area. The owners of self-build house 1 had further plans to modify and extend their house – according to them, self-build houses are never quite finished.